29.02.2016 | News

Given that the summit of Scotland’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis, is only 1344 m above sea level, this country is not immediately associated with avalanches or the need for a warning service. Does it snow in Scotland? Do any avalanches occur there? Anyone who takes an interest in the satellite images that are captured above Europe is likely to have noticed that there is no lack of precipitation or wind in Scotland. But how much is known about the temperatures recorded at the relevant altitudes? At low altitudes most of the precipitation falls as rain, but there is frequent snowfall on the summits in wintertime, so that all the ingredients for avalanches exist. And there are plenty of winter sports enthusiasts exposed to the dangers which threaten. Hundreds of them take to the outdoors in any and all weather conditions, ordinarily armed with ice axes.

What is the purpose of avalanche warning experts getting together?

Why would a Swiss avalanche forecaster spend time in Scotland? We possess sufficient mountain resources here at home for learning the advanced skills required for snow profiling, weather analysis and avalanche danger assessment. As illustrated by a comparison of Scotland and Switzerland, however, avalanche warning experts can always learn something new from their counterparts elsewhere. A maritime climate prevails in Scotland, and persistent weak layers in the snowpack are rare, but the avalanche situation can nonetheless change dramatically within just a few hours. Outdoor activities there generally take place in extremely steep terrain, so that most of the deaths recorded in avalanche accidents result from injuries sustained in falls. Communities and transportation routes are seldom endangered. In Switzerland, in contrast, distinct weak layers in the snowpack can persist for long periods throughout the winter. The most common cause of death among avalanche victims here is asphyxiation because of burial, and avalanches can claim the lives of winter sports enthusiasts in a wide variety of terrains. In the event of very heavy snowfall, roads have to be closed and settlements evacuated. Thus, the contrasts between the two countries are huge, but in each case there is the urgent desire to warn tourists of avalanche dangers on the basis of sound information. Although difficult, it is essential to issue such warnings using language that is readily understandable by all those who engage in winter sports and reference a broadly comparable scale – the standardised European avalanche danger scale – because today's mountain sports enthusiasts regularly venture far beyond their familiar home territory. During the winter they can be found freeriding in St. Anton, undertaking weekend tours in the mountains at home, spending five days climbing the ice on Ben Nevis, and visiting Lofoten for a week's touring in April. A reciprocal exchange among avalanche warning experts and the sharing of knowledge on the specific challenges that exist in their territories bring about a more consistent application of the European avalanche danger scale.

Other benefits also arise, however, when experts get together to learn from each other. A Scot visiting Switzerland, for instance, has the opportunity to find out about advanced techniques for analysing weak layers, and a Swiss forecaster in Scotland can gain experience in responding to rapidly changing weather conditions. Norwegians, in turn, can benefit from our avalanche warning operations and experience, but also, as members of a recently established warning service, deliver valuable insights and fresh ideas because they are approaching the subject without any historical constraints.

What can the Swiss learn from the avalanche service in Scotland?

That was precisely the question I was asking myself as I set off for Aviemore in the Scottish Highlands to meet Mark Diggins, the coordinator of the Scottish Avalanche Information Service. I had been anticipating inhospitable weather with lots of wind and rain, but as we ascended the Cairn Gorm funicular railway – which, but for the livery, resembles the Parsennbahn railway – conditions on the Cairn Gorm summit at 1245 m were remarkably calm, but nonetheless cold. We had left our skis at the bottom for the simple reason that there was insufficient snow for ski touring. We scrambled over the summit to reach an east facing slope in the lee of the plateau. While we were hiking, Mark told me that a gust of wind had once carried him over a crag here before the very eyes of a group of students. After falling approximately 20 m, he was able to grab hold of the rock and await rescue. The tour took us to a profile site where more than enough snow – more than 3 m deep, of which the bottom 2.5 m were hard and consolidated – was lying for us to assess a profile. Embedded in the snow near the surface was a weak layer containing graupel, but there was no indication of avalanche danger.

After walking on, we reached a basin where the landscape was dominated by rock walls and couloirs. And peopled by an enormous variety of climbers, skiers and hikers. I was astonished at the sheer size of the crowd! Until that moment I had not given any thought to avalanche risks, but I suddenly realised that a warning service was essential here. The key factor when assessing avalanche hazards is whether or not a release can be triggered by people. Avalanche size is far less relevant, since avalanches will almost invariably have serious consequences, irrespective of their size. The terrain here is either flat or extremely steep – very few slopes qualify as 'only' steep. It is very difficult to describe the conditions that prevail in Scotland with the tools provided by the European avalanche danger scale.

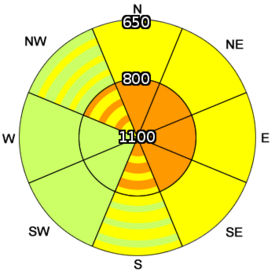

There is another valuable lesson I learned while in Scotland: the Scots are utterly unflappable. They remain unperturbed when confronted with a European tourist driving on the wrong side of the road, a 70 mph / 112 km/h wind (which calls for the ice axe to be used as a ground anchor), or even a European avalanche danger scale. In order to describe the particular conditions that arise in the Highlands by implementing the European avalanche danger scale, the Scots apply their own, additional concept of 'localised hazard'. This way of describing the danger together with the specific local hazard is presented in a hazard rose (cf. Fig. 3). To those unfamiliar with the Scottish mountains, this may appear to be a rather strange solution, but those who have experienced the region first-hand realise that it makes sense. Meetings between avalanche warning experts therefore foster not only the exchange of knowledge, but also enhance mutual understanding.

Copyright ¶

WSL and SLF provide the artwork for imaging of press articles relating to this media release for free. Transferring and saving the images in image databases and saving of images by third parties is not allowed.

Contact ¶

Links and documents ¶

Avalanche information resources in Scotland

- Avalanche reports, weather forecasts, snow profiles, avalanche activity and blogs on the current conditions: Avalanche Information for the Scottish Mountains